|

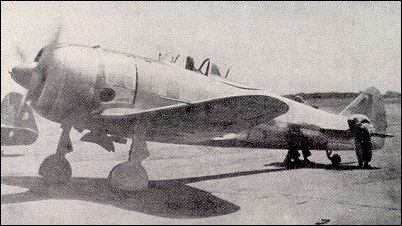

| Of similar general configuration to the

Ki-43, the Nakajima Ki-44 prototypes

incorporated the manoeuvring flaps

that had been introduced on that aircraft,

and carried an armament of two

7.7mm and two 12.7mm

machine-guns. First flown in

August 1940, the Ki-44 was involved in

a series of comparative trials against

Kawasaki's Ki-60 prototype, based on

use of the Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine,

and an imported Messerschmitt

Bf 109E. The result of this evaluation,

and extensive service trials, showed

the Ki-44 to be good enough to enter

production, and it was ordered under

the designation Army Type 2 Singleseat

Fighter Model 1A Shoki (demon),

company designation Ki-44-Ia, which

carried the same armament as the prototypes.

A total of only 40 Ki-44-I aircraft

was produced, including small

numbers of the Ki-44-Ib armed with

four 12.7mm machine-guns,

and the similar KI-44-Ic with some

minor refinements.

When introduced into service the

high landing speeds and limited manoeuvrability

of the Shoki made it unpopular

with pilots, and very soon the

Ki-44-II with a more powerful Nakajima

Ha-109 engine was put into production.

Only small numbers of the Ki-

44-IIa were built, the variant being followed

by the major production Ki-44-

Ilb. The Ki-44-IIc introduced much

heavier armament, comprising four 20mm cannon or, alternatively, two 12.7mm machine-guns and two 40mm cannon, and these proved to be

very effective when deployed against

Allied heavy bombers attacking Japan.

Final production version was the Ki-44-

III with a 1491kW Nakajima

Ha-145 radial engine, an increase m

wing area and enlarged vertical tail

surfaces.

Nakajima had built a total of 1,225

Ki-44s of all versions, including prototypes,

and these were allocated the

Allied codename 'Tojo'. They were

deployed primarily in Japan, but were

used also to provide an effective force

of interceptors to protect vital targets,

as in Sumatra where they defended

the oil fields at Palembang.

| MODEL | Ki-44-IIb |

| CREW | 1 |

| ENGINE | 1 x Nakajima Ha-109, 1133kW |

| WEIGHTS |

| Take-off weight | 2995 kg | 6603 lb |

| Empty weight | 2105 kg | 4641 lb |

| DIMENSIONS |

| Wingspan | 9.45 m | 31 ft 0 in |

| Length | 8.8 m | 29 ft 10 in |

| Height | 3.25 m | 11 ft 8 in |

| Wing area | 15 m2 | 161.46 sq ft |

| PERFORMANCE |

| Max. speed | 605 km/h | 376 mph |

| Ceiling | 11200 m | 36750 ft |

| Range w/max.fuel | 1700 km | 1056 miles |

| ARMAMENT | 4 x 12.7mm machine-guns |

| A three-view drawing (752 x 1176) |

| Ron, e-mail, 23.04.2014 09:27 The Shoki was a good match for the Spit VIII, the P-51A, and the F6F as well as the P-38. An RAF Spitfire Mk VIII pilot over Burma even dove and zoom climbed to 18,000' and was alarmed to see the pursuing Japanese fighter could stay right with him. It was the Ki 44!

The Shoki was considered an equal challenge to these Allied fighters as a dogfighter with the combat flaps - in addition to it's vertical prowess.

It was not maneuverable enough only by Ki 43 Hayabusa standards.

Not only that, it also tackled Allied bombers with far more success than the lightly armed Ki 43. reply | | Miguel Junior, e-mail, 02.04.2013 22:59 In fate, the Ki-44, like Ki-100 and Kawanishi N1K1, have only one serius problem: the lack of pilots...

Best regards,

Miguel Junior

''''''''''''' reply |

| steve, e-mail, 04.08.2012 02:44 If the Granville brothers (GeeBees) had designed a fighter, it likely would've looked like the Ki-44 - an engine with wings! reply | | Ron, e-mail, 27.04.2012 03:17 I understand some P-51s could turn at least as well as the standard Shoki. reply | |

| | Ron, e-mail, 13.04.2012 07:36 Despite inferior maneuverability to it's stable mate (Ki43), the Shoki 'won the approval of pilots. They especially liked ...ki 44's spin performance and lateral stability' as a more focussed gun platform when firing. I think moving the tail fin back ala the Zero helped because that is why the A6M did that - to keep the wing cannons from spraying left and right so much.

With a dive performance between the P-39 and P-40 and a climb like the P-39 and Spitfire, it could still be more competetive than the Hayabusa. And the Allies thought it was maneuverable if not the Japanese. It had those combat flaps too so don't let wing-loading fool you. For all I know it didn't suffer from an unreliable powerplant like all the newer Japanese fighters that followed (Tony, Jack, Frank, and George). That's a biggie. reply | | Aaron, e-mail, 12.06.2011 19:33 Hey blue and devin,

I gave up studying English and Literature in 1973 when I graduated college. I like Star Wars and Star Trek but we are not discussing fiction on this sight. I suggest youall

read that there first listing of blue's there. You know what I mean. That there "The reformation of manners",1678-1790. reply | | bombardier, e-mail, 24.05.2011 19:04 Imagine a B-29 being hit by 2 40mm cannons reply | | blue, 18.04.2011 21:09 "The reformation of manners", 16781790

2.5.4 Fiction as a new experimental field, 17001800

2.5.5 The novel as national literature, 19th-century developments

2.5.6 Pushing art to its limits: Romanticism, 17701850

2.5.7 "Realism" and the reevaluation of the past and the present, 17901900

2.5.8 Explorations of the self and the modern individual, 17901930

2.6 The novel and the global market of texts: 20th- and 21st-century developments

2.6.1 Writing literary theory

2.6.2 Writing world history

2.6.3 Writing for the market of popular fiction

3 See also

3.1 Genres of the novel

3.2 Literature

3.3 Novels-related articles

4 Notes

5 Further reading

5.1 Contemporary views

5.2 Secondary literature

[edit] Definition

Gerard ter Borch, young man reading a book c.1680, the format is that of a French period novel.

Madame de Pompadour spending her afternoon with a book, 1756 religious and scientific reading has a different iconography.

Winslow Homer, The New Novel (1877), again reading in a relaxed position

Urban commuter reading a novel, Berlin 2009.

The fictional narrative, the novel's distinct "literary" prose, specific media requirements (the use of paper and print), a characteristic subject matter that creates both intimacy and a typical epic depth can be seen as features that developed with the Western (and modern) market of fiction. The separation of a field of histories from a field of literary fiction fueled the evolution of these features in the last 400 years.

[edit] A fictional narrativeFictionality and the presentation in a narrative are the two features most commonly invoked to distinguish novels from histories. In a historical perspective they are problematic criteria. Histories were supposed to be narrative projects throughout the early modern period. Their authors could include inventions as long as they were rooted in traditional knowledge or in order to orchestrate a certain passage. Historians would thus invent and compose speeches for didactic purposes. Novels can, on the other hand, depict the social, political, and personal realities of a place and period with a clarity and detail historians would not dare to explore.

The line between history and novel is eventually drawn between the debates novelists and historians are supposed to address in the West and wherever the Western pattern of debates has been introduced: Novels are supposed to show qualities of literature and art. Histories are by contrast supposed to be written in order to fuel a public debate over historical responsibilities. A novel can hence deal with history. It will be analyzed, however, with a look at the almost timeless value it is supposed to show in the hands of private readers as a work of art.

The critical demand is a source of constant argument: Does the specific novel have these "eternal qualities" of art, this "deeper meaning" an interpretation tries to reveal? The debate itself had positive effects. It allowed critics to cherish fictions that are clearly marked as such. The novel is not a historical forgery, it does not hide the fact that it was made with a certain design. The word novel can appear on book covers and title pages; the artistic effort or the sheer suspense created can find a remark in a preface or on the blurb. Once it is stated that this is a text whose craftsmanship we should acknowledge literary critics will be responsible for the further discussion. The new responsibility (historians were the only qualified critics up into the 1750s) made it possible to publicly disqualify much of the previous fictional production: Both the early 18th-century roman ΰ clef and its fashionable counterpart, the nouvelle historique, had offered narratives with by and large scandalous historical implications. Historians had discussed them with a look at facts they had related. The modern literary critic who became responsible for fictions in the 1750s offered a less scandalous debate: A work is "literature", art, if it has a personal narrative, heroes to identify with, fictional inventions, style and suspense in short anything that might be handled with the rather personal ventures of creativity and artistic freedom. It may relate facts with scandalous accuracy, or distort them; yet one can ignore any such work as worthless if it does not try to be an achievement in the new field of literary works[1] it has to compete with works of art and invention, not with true histories. The new scandal is if it fails to offer literary merits.

Historians reacted and left much of their own previous "medieval" and "early modern" production to the evaluation of literary critics. New histories discussed public perceptions of the past the decision that turned them into the perfect platform on which one can question historical liabilities in the West. Fictions, allegedly an essentially personal subject matter, became, on the other hand, a field of materials ... reply | | devin, 18.04.2011 21:08 The fictional narrative, the novel's distinct "literary" prose, specific media requirements (the use of paper and print), a characteristic subject matter that creates both intimacy and a typical epic depth can be seen as features that developed with the Western (and modern) market of fiction. The separation of a field of histories from a field of literary fiction fueled the evolution of these features in the last 400 years.

[edit] A fictional narrativeFictionality and the presentation in a narrative are the two features most commonly invoked to distinguish novels from histories. In a historical perspective they are problematic criteria. Histories were supposed to be narrative projects throughout the early modern period. Their authors could include inventions as long as they were rooted in traditional knowledge or in order to orchestrate a certain passage. Historians would thus invent and compose speeches for didactic purposes. Novels can, on the other hand, depict the social, political, and personal realities of a place and period with a clarity and detail historians would not dare to explore.

The line between history and novel is eventually drawn between the debates novelists and historians are supposed to address in the West and wherever the Western pattern of debates has been introduced: Novels are supposed to show qualities of literature and art. Histories are by contrast supposed to be written in order to fuel a public debate over historical responsibilities. A novel can hence deal with history. It will be analyzed, however, with a look at the almost timeless value it is supposed to show in the hands of private readers as a work of art.

The critical demand is a source of constant argument: Does the specific novel have these "eternal qualities" of art, this "deeper meaning" an interpretation tries to reveal? The debate itself had positive effects. It allowed critics to cherish fictions that are clearly marked as such. The novel is not a historical forgery, it does not hide the fact that it was made with a certain design. The word novel can appear on book covers and title pages; the artistic effort or the sheer suspense created can find a remark in a preface or on the blurb. Once it is stated that this is a text whose craftsmanship we should acknowledge literary critics will be responsible for the further discussion. The new responsibility (historians were the only qualified critics up into the 1750s) made it possible to publicly disqualify much of the previous fictional production: Both the early 18th-century roman ΰ clef and its fashionable counterpart, the nouvelle historique, had offered narratives with by and large scandalous historical implications. Historians had discussed them with a look at facts they had related. The modern literary critic who became responsible for fictions in the 1750s offered a less scandalous debate: A work is "literature", art, if it has a personal narrative, heroes to identify with, fictional inventions, style and suspense in short anything that might be handled with the rather personal ventures of creativity and artistic freedom. It may relate facts with scandalous accuracy, or distort them; yet one can ignore any such work as worthless if it does not try to be an achievement in the new field of literary works[1] it has to compete with works of art and invention, not with true histories. The new scandal is if it fails to offer literary merits.

Historians reacted and left much of their own previous "medieval" and "early modern" production to the evaluation of literary critics. New histories discussed public perceptions of the past the decision that turned them into the perfect platform on which one can question historical liabilities in the West. Fictions, allegedly an essentially personal subject matter, became, on the other hand, a field of materials that call for a public interpretation: they became a field of cultural significance to be explored with a critical and (in the school system) didactic interest in the subjective perceptions both of artists and their readers. reply | | Ron, e-mail, 07.11.2010 07:12 4x20-mm HO-3 cannon! Ha-109 reliable engine!

But alas. No flick moves or snap rolls like the Oscar.

The Tojo will punish such aerobatics. What could replace them both at the right time - midwar?

So what would be the harm of an Oscar with that Ha-109 engine and 4 HO-3 cannon? Just as a reliable stable-mate for the unreliable Tony and Frank later.

It could have the fuselage of the Tojo with the wings and tail of the Oscar. Imagine an Oscar that can dive fast and decimate bombers! Or is it a Tojo without vices in a dogfight?

Or do you just put them both in the same battles as they were? I think it's better minus the weaknesses of both.

But that's fantasy. I know the J2M5 and the Ki 100 fill the bill - but way too few and at curtain time besides. reply |

| Aaron, e-mail, 07.10.2010 06:48 The Ki.44 was probably the first Japanese fighter that clearly outclassed the contemporary P-40. It could out accelerate, outclimb and dive with it more or less. I do not have any official documents on its ability to turn or roll but I have see a few articles that liken the Shoki to the FW-190A and the power to weight ratio was definitely in the Ki.44's favor. I am a firm believer, if Nakajima had dropped the Oscar and concentrated on the Tojo the Army boys would have had a much rougher time. reply | | Aaron, e-mail, 19.09.2010 03:43 My mistake, I meant the Ki.44 would outperform the Ki.84 not the Ki.43. I just finished an addition to the Oscar and got my wires crossed, sorry. reply | | Aaron, e-mail, 19.09.2010 03:40 According to Yadika and William Green a few Ki.44-IIIa aircraft had been delivered to the JAAF by January 1945. The Ki.44-IIIa carried 4x20mm cannons and an engine capable of 1800-2000hp. If anyone has more information on the engine and especially on performance of this model, I would very much like to know. The Ki.44-III's loded weight is listed at 6362lbs. and the Ki.84-1a's loaded weight is about 7965lbs. This is just an opinion, but I believe the Ki.44 would outclimb, out accelerate and out roll the Ki.43 at 2,000hp. The Ki.84 would probably have a slightly higher top speed due to its cleaner lines, but who knows? No really, who does know? I'm all ears and eyes. reply | | Aaron, e-mail, 17.09.2010 01:02 On a confidential military sheet listing Japan's fighters and titled COMPARATIVE PERFORMANCE AND CHARACTERISTICS REPRESENTATIVE ENEMY AND ALLIED AIRCRAFT, the following is listed for the TOJO 2 type 2 Nakajima (Ki.44-II):

Engine: Nakajima type 2. 1500hp /S.L. 1300hp /17,200ft.

Armament: 4x12.7mm. Maximum Range: 1,050mls /166mph.

Radius of action 195mls. /197gallons of fuel.

Test weight (6,100lbs.) performance follows: Climb: 3940fpm /S.L. 3400fpm /17,200ft. 10,000ft /2.5min. 20,000ft /5.5min. Maximum climb around 5000ft /is about 4100fpm. Service ceiling is listed as 36,500ft. Maximum speed is listed as: 325mph /S.L. 376mph /17,200ft. No attached info on the conditions of testing given. Does anyone have any official information about turn time, turn circle or roll rate? To date, all I have come up with is published coments that the Shoki rolled much like the Fw-190A. reply | |

| | Jackie, 09.08.2010 05:11 The Nakajima Ki-44 Tojo entered service in 1942. The pilots disliked the Tojo because its less maneuverable than its predecessor, the nimble Ki-43, and pilots disliked its poor visibility on the ground, its higher landing speed, and severe restrictions on maneuvering. However,the Ki-44 proved to be superior in flight tests.It was an outstanding interceptor and could match Allied types in climbs and dives, giving pilots far more flexibility in combat. And, its arnament( some versions have Ho-301,103,5 or 203 cannons) was far more deadly than the Ki-43's two 12.7mm machines guns. These make it an effective bomber destroyer and was used to intercept and destroy the B-29 Superfortresses in the last months of the war. But poor pilot training in the last part of the conflict often made them easy targets for Allied pilots. Some were used as kamikaze aircraft in the last part of the conflict. The 47th Sentai based at Narimasu airfield even used bomber collision tactics against the B-29s during the defense of Tokyo. reply | | Ron, e-mail, 25.05.2010 09:22 Does someone know the reliability of the Ha-109 engine?

I wonder when the Ha-112 was available. Like the Ha-109 it was a bomber engine. The -112 was very reliable and not so bulky. It was chosen for the successful Ki-100 Tony radial.

Perhaps the Tojo's -109 predates it although they both have 1500 hp on take off. Can you imagine a Tojo with the streamlined cowl of the Ki-100? Granted, the fighter body designs are years apart. However the engines could have been of the same 'generation' since the hp was so close. reply | | Ronald, e-mail, 16.07.2009 09:38 My favorate Shoki is the Ki 44-IIc variant with four 20-mm Ho-3 cannon. These preceeded the famous rapid fire 20-mm Ho-5 used in the Ki-44-III and subsequently on all IJA fighters. The Ho-3 was slow but had far more velocity and a much heavier shell. This would complement it's bomber interceptor role more than dog fighting other fighters. Unfortunately the bulk of Shoki production was only armed with 4 fast Ho-103 MGs (12.7-mm) favoring a dog fighter due to a denser pattern of fire but far less striking power. They say it was a worthy opponent for the P-38. If only the IJN Raiden had visibility from the cockpit like the Shoki! reply | | ulf larsson, e-mail, 27.05.2009 22:22 Very nice aircraft,seems to me very powerful too,by

judging from its nickname it must be.It must have been scary in the eyes of enemy pilots.

With kindly regards.Ulf Larsson reply | | Hiroyuki Takeuchi, e-mail, 30.01.2009 03:53 Yes. Shoki is no demon. He destroys demons. Shoki is the figure on the tiger in the painting below.

ja.wikipedia.org /wiki /%E3%83%95%E3%82%A1%E3%82%A4%E3%83%AB:Gyosai_The_Tiger.jpg

Also, the widespread error in subtype defintion should be corrected. The IIb is armed by two 12.7mm nose guns only and could carry two 40mm cannons in the wings as "special equipment". The IIc was armed with four 12.7mm guns. No 20mm guns were ever fitted in any production Ki44s. Also, there is no evidence that the Ki44III ever got beyond the prototype stage. reply | | Chinese-pilot, 29.12.2008 12:44 Shoki(ΔΑΨP) is a ghostbuster in the Chinese story. reply |

|

Do you have any comments?

|

|

COMPANY

PROFILE

All the World's Rotorcraft

|

Ron

Ron

Spot On Miguel, The thing that haunted the Japanese later in the war was the quality of their airmen. Victims to some extent not only Allied aircraft, but also by the Bushido code. So concerned were these airmen to not bring dishonor onto their families, that they needlessly squandered their lives in suicidal attacks just to stave off capture. Even when their capture wasn't imminent. I imagine I flight of Ki-44's in the hands of experienced and seasoned pilots would have been quite formidable.

reply