|

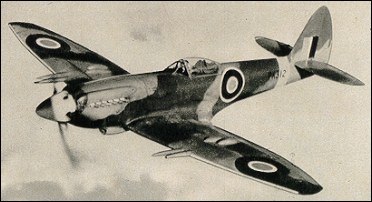

| Without doubt the best known British aircraft of World War II, the Supermarine Spitfire originated

from the Type 224 designed by R. J. Mitchell to meet the requirements of Specification F.7/30. A cantilever low-wing monoplane of all-metal construction, it had an inverted-gull wing and 'trousered' fixed main landing gear, and was powered by a 447kW Rolls-Royce Goshawk II Vee engine. When the Type 224 was tested its performance proved disappointing, and it was no more successful than any of the other submissions to this specification; none of them gained an Air Ministry contract.

Given a free hand to design a new single-seat fighter unfettered by official specifications, Mitchell outlined on his drawing board the delightful Type 300. Smaller, sleeker and with drag-reducing retractable landing gear, it was tailored around the new Rolls-Royce P.V.12 (Merlin) engine; the wings were not only of distinctive elliptical shape, but they housed eight machine-guns, all of them firing outside the propeller disc. Air Ministry Specification F.36134 was drawn up around the Type 300 and a prototype was ordered. It was powered by a 738kW Rolls-Royce Merlin C and flew for the first time on 5 March 1936. Comparatively little flight testing was needed to confirm it as a winner, and its superb handling qualities and performance resulted in a first contract (for 310 Spitfire Mk I aircraft) being awarded on 3 June 1936. However, planned mass production was slow to gain momentum and it was not until July 1938 that the first Spitfire Mk I reached No. 19 Squadron at Duxford; only five had been delivered by the time of the Munich crisis in September of that year, but the trickle was eventually to become a flood that totalled 20,334 Spitfires and 2,556 related new-build Seafire naval fighters. A degree of multi-role capability was to result from the development of low-altitude clipped wings (prefix LF), and high-altitude increased-span wings (HF), the standard wing being identified as F, and with variations of armament within these wings comprising eight machine-guns (suffix A), two cannon and four machine-guns (B), four cannon (C) and two cannon, two 12.7mm machine-guns and up to 454kg of bombs (E).

By the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, the RAF had nine operational Spitfire squadrons, and on 16 October 1939 a Spitfire of No. 603 Squadron claimed the first German aircraft to be destroyed over the UK in World War II, a Heinkel He 111. By August 1940, shortly before the Battle of Britain reached its climax, RAF Fighter Command could call upon 19 Spitfire Mk I squadrons. By December 1940 Spitfire Mk IIs were carrying out 'Rhubarb' sweeps over occupied Europe, and the first to serve overseas were Spitfire Mk VBs flown to Malta from HMS Eagle on 7 March 1942.

Soon after that date the same mark was operational in the Middle East, and by early 1943 the first Spitfire Mk Vs were arriving in the Pacific theatre. In growing numbers and with increasing capability the Spitfire served throughout World War II, not only with the RAF but with the nation's allies, including US and Soviet squadrons. It also had the distinction of remaining in production throughout the entire war and was operational post-war, the last mission flown by a photo-reconnaissance Spitfire PR.Mk 19 of No. 81 Squadron in Malaya on 1 April 1954.

| A three-view drawing (592 x 919) |

| MODEL | Spitfire Mk VA |

| ENGINE | 1 x Rolls-Royce Merlin 45, 1102kW |

| WEIGHTS |

| Take-off weight | 2911 kg | 6418 lb |

| Empty weight | 2267 kg | 4998 lb |

| DIMENSIONS |

| Wingspan | 11.23 m | 37 ft 10 in |

| Length | 9.12 m | 30 ft 11 in |

| Height | 3.02 m | 10 ft 11 in |

| Wing area | 22.48 m2 | 241.97 sq ft |

| PERFORMANCE |

| Max. speed | 594 km/h | 369 mph |

| Ceiling | 11125 m | 36500 ft |

| Range w/max.fuel | 1827 km | 1135 miles |

| ARMAMENT | 8 x 7.7mm machine-guns |

| Jan, e-mail, 18.03.2024 22:06 Ten Things You Learned In Kindergarden That'll Help

You With Most Popular Pornstars Most Popular Pornstars reply | | Ben De Bie, 09.02.2017 10:48 This is my grandfather's favourite aircraft! :) Greate site! reply |

| Ron, e-mail, 02.03.2015 13:49 How to improve the Spit?

Invert the fuel injected engine and build in a 20mm motor cannon to fire through the nose like it was designed to do in French fighters. This would improve view over a more sloped nose, give better dive, easier to recock a jammed cannon in the air and it doesn't freeze. Long range accuracy of a powerful central cannon fully harnesses the strengths of the Hispano.

If the RR engine can't accommodate it, make a twin-engined Spitfire (Whirlwind style). Put 3 or 4 Hispanos in the center nacelle with the ammo at the cg. Torque could be neutralized, improving stall performance.

Long-range could easily be improved with more room for petrol. Add Fowler flaps to restore aerobatics of the smaller forebearer. Enlarge wing, elevator and tail surfaces as well for that purpose. Top it with a bubble canopy.

No more weak initial dive.

No more range limits beyond point interception.

No more dicey stall-turn. No torque.

No more narrow wheel struts.

No more restricted view all-around.

No more weak MGs, but a nose all-cannon battery.

No more jammed cannon. reply | | craige hume, e-mail, 12.11.2014 14:30 could you send me a free modal of a spitfire at nr32 2bw Norwich rd lowestoft reply | |

| | Ron, e-mail, 09.09.2014 08:07 Give credit to Anthony Cooper and his 'Darwin Spitfires' site.

The test was done by the RAAF in August 1943.

His stall chart didn't translate too well here though.

A hard turn in the MkVcT (6G) had a stall of 212 mph clean (or 184 knots IAS);

@ 20,000' stall was 296 mph TAS;

@ 30,000' it was 338 mph.

349 mph was the maximum level speed @ 30,000' so no wonder the incidence of accelerated stall was high at Darwin!

Not being familiar with knots, I used 1.15078 for mph calculation. reply | | Sven, 31.08.2014 22:44 Ron.That was an epic!

Many thanks for a well researched

and well presented post. It makes it worth looking

here once in a while. reply | | Ron, e-mail, 31.08.2014 09:28 Mk Vc vs Zero 32:

Thus it is doubly ironic that the Spitfire's reputation would habitually be established by reference to archaic, non-tactical criteria, and that the new Japanese opponent would trump every one of the Spitfire's purported trademark virtues: in effect, 'whatever you can do, I can do better'.

However, despite the gloomy overall assessment provided by the comparative tests, the relative situation was not unfavourable to the Spitfire. Given that the strong fighter and AA defence over Darwin forced the Japanese to penetrate Australian airspace above 25 000 feet, the Zeros were thereby forced to play to the Spitfire's strengths. Moreover, given the tactical situation of intercepting bomber formations, the Spitfires would generally be coming down in a high speed dive, which was also advantageous. 1 Fighter Wing's recommended tactics at this point were correct: either to zoom back up after firing or disengage by continuing the high speed dive downwards. Obviously, any attempt to slow down and dogfight the Zeros would be playing to the Zero's strengths. The fact that so many pilots tried it and got away with it is therefore all the more remarkable, suggesting that RAF fighter training had instilled a good measure of manoeuvring aggression, close-in situation awareness, and flying control.

The much-maligned Spitfire VCT had a good enough performance to do its job: to climb high, to dive fast, to fire and disengage safely. Indeed, in these respects it had similar tactical characteristics to other early-war allied fighter aircraft - such as the P-39, P-40, and F4F Wildcat – in that it possessed a clear superiority in one tactical mode: diving fast into the attack and then performing rolling downward evasion. On top of that, it shared with the F4F the ability to climb above 30 000 feet – the tactical vantage point from which attacks were delivered. These were its most relevant tactical characteristics. In that sense, the Spitfire was no more and no less than a typical allied fighter of the earlier part of World War II – good enough to do its job, but not good enough to establish superiority over the enemy.

[1] Ivan Southall (1958) Bluey Truscott, Sydney, p.153-156.

[2] 14, 17-18.8.1942.

[3] NAA A11093: 452 /A58 PART 1.

[4] NAA A11093: 452 /A58 Part 1.

[5] NAA A1196 1 /501 /505.

[6] NAA A1196: 1 /501 /505.

The RAAF P-40 fared no worse against the Zero 21, 32, and Oscar at Darwin than the tropicalized Spitfire Vc. The Kittyhawk even out-accelerated it! reply | | Ron, e-mail, 31.08.2014 09:09 I had to continue the RAAF Spit vs Zero test at Darwin due to it's length:

...In a modest 3G turn, the Spitfire would stall at 130 knots IAS, which equates to a TAS of 242 knots at 20 000 feet. At 6G (a hard turn or pull out at high speed, with the pilot blacking out), the Spitfire stalled at 184 knots IAS, which equated to 257 knots TAS at 20 000 feet, and 294 knots at 30 000. The latter was only 11 knots less than the Spitfire's maximum speed at that height (at the emergency power settings of 3000 rpm and plus 2 ½ pounds boost), so it is clear that as height increased, the pilot found himself stuck in an increasingly narrow corner of the flight envelope, until any attempt to pull G would result in an instant high speed stall. This helps to explain the high incidence of Spitfires stalling and spinning out of combat turns over Darwin in 1943.

Spitfire VC Stalling Speeds[4]

G

Stall IAS, knots

Stall TAS 20 000 feet

Stall TAS 30 000

feet

1

73

103

118

2

107

150

172

3

130

182

208

4

150

210

239

5

167

234

268

6

184

257

294

7

199

279

319

8

212

297

340

By contrast, the Zero's lighter weight meant that it would always be superior in all tight manoeuvres. Obviously, the Zero also stalled out under G, but the tests showed it to have superb handling characteristics in hard turns, with no tendency to spin out of high speed stalls (implying that it was superior to the Spitfire in this respect). Although Spitfires endeared themselves to pilots by their sweet flying qualities, it is clear that the Zero too had impeccable manners.

If a Spitfire followed a Zero around in a loop, it would stall out at the top, and could only stay behind the Zero for Ύ of a horizontal turn. In short, it was too easy for a Zero to evade a Spitfire at medium altitudes and below, by simply performing any vertical manoeuvre or hard turn. This meant it would be very difficult for a Spitfire to get a shot at a manoeuvring Zero. The only practical firing opportunity for Spitfire pilots would come in a bounce.

Neither aircraft had a good roll rate at high speed, due to their ailerons locking almost solid in the airflow. However, in this respect the Zero was even worse than the Spitfire, which permitted a glimmer of encouragement for the Spitfire pilot: the Zero could not get into a firing position behind the Spitfire if the latter evaded in diving aileron turns at high speed. Other than the downward break, no other evasive manoeuvre by the Spitfire was likely to work, although a vertically-banked climbing turn was difficult for the Zero to follow. Otherwise, the Zero could follow the Spitfire through any manoeuvre below 220 knots, and could use its slow turning advantage to get onto the Spitfire's tail after 2 ½ hard turns.

It was only at higher speeds that the Spitfire started to enjoy a relative advantage. Because the Zero's controls stiffened up even more rapidly than the Spitfire's, the Zero had great difficulty in following the Spitfire through high speed manoeuvres where the pilot pulled a lot of G. From about 290 knots, the Zero had great difficulty following the Spitfire through diving aileron rolls. The conclusion was that the Spitfire was more manoeuvrable above 220 knots, while the Zero was the better below that speed. Reflecting this set of opposite characteristics was the fact that the Zero's standard evasive manoeuvre was the very opposite to that of the Spitfire – upwards rather than downwards, in the form either of a climbing turn or a vertical aerobatic manoeuvre like a loop, stall turn or Immelmann.

Overall, the summary from the comparative trials was not encouraging:

'Both pilots consider the Spitfire is outclassed by the Hap at all heights up to 20 000 feet…The Spitfire does not possess any outstanding qualifications which permit it to gain an advantage over the Hap in equal circumstances.'[5]

The conclusions of Wawn and Jackson only corroborated the earlier evaluation conducted by 1 Fighter Wing HQ[6] after combat experience over Darwin, which found that the Spitfire had a higher maximum speed, that it was more manoeuvrable at high speed, and that it could be dived to a greater speed. It followed that the only sensible offensive tactics were the dive from height followed by a zoom climb for a re-attack. The recommended evasive tactic when under attack was to break downwards into a vertical dive at full power, while yawing the aircraft violently by uncoordinated use of the rudder and /or ailerons to put the Zero pilot off his aim. Once the speed had built up (presumably 300 knots), the pilot should start rolling into downward aileron turns to obtain a clean separation from the Zero.

Rightfully, a whole generation of pilots learned to treasure the Spitfire for its delightful response to aerobatic manoeuvres and its handiness as a dogfighter. However, it is odd that they had continued to ... reply | | Ron, e-mail, 31.08.2014 08:32 I'll insert this RAAF Spitfire vs Hamp comparison test:

The Model 32 Zero, with its squared-off wingtips, was regularly encountered both over Darwin and New Guinea in 1943. Known to the allies by the reporting name 'Hap' to distinguish it from the round-wingtipped 'Zeke', the Model 32 was an improved model over the original Model 21 with which the Imperial Japanese Navy had fought its 1941-42 air offensives. The chief difference lay in its more powerful Mitsubishi Sakae 21 engine, which developed 1130 hp (as compared with 940 hp in the Model 21). The more powerful engine was heavier, requiring a reduction in fuel capacity from 518 litres to 470, and more thirsty; thus range was less than that of the earlier model. Both the newer and older types were encountered over Darwin.

Nonetheless, it was a Model 32 Zero that was captured and rebuilt, permitting the trials to occur in August 1943. The 1130hp of the Model 32's Sakae 21 engine was quite comparable to the 1210 hp of the Spitfire's Merlin 46, but the Model 32's weight was much less – 5155 lb compared to the Spitfire's 6883 lbs. As a result of this structural lightness, the Zero had both a superior power loading (4.5 lb /hp versus 5.6 lb /hp) and a lower wing loading (22 lb /ft2 versus 28 lb /ft2).

These differing technical characteristics determined the pattern of relative performance between the two machines, as shown by the tactical trials conducted by two experienced RAAF fighter pilots in flying trials conducted over three flying days[2]. Flight Lieutenant 'Bardie' Wawn DFC and Squadron Leader Les Jackson DFC flew against one another in both aircraft, and what they found was not encouraging.

They found that the Zero had a lower rated altitude than the Spitfire, 16 000 feet against 21 000 feet, which delivered the Spitfire a good speed advantage at height – it was 20 knots faster at 26 000 feet. However, as had already been noted by RAF Fighter Command in Europe, the Spitfire had relatively slow acceleration, and thus the Zero was able to stay behind the Spitfire within gun range while the Spitfire gradually accelerated away out of range. Even in a dive the Spitfire still accelerated too slowly to avoid the Zero's gunfire. Climbing away was also not an option, as the Spitfire's climb superiority was too slight (not to mention the slow acceleration problem once again).

The only offensive solution for the Spitfire was to attack from a height advantage, to maintain a high IAS on the firing pass, to fight on the dive and zoom, and to pull high speed G. Slowing down, or being caught while flying slowly, would clearly be very dangerous, for the Spitfire would be unable to evade. Above 20 000 feet, so long as the Spitfire started with a 3-4000 feet height advantage, the Spitfire could make dive and zoom attacks with impunity.

The height advantage of the Spitfire VC was also shown by the British machine's superior operational ceiling. Wawn and Jackson established 32 500 feet as the 'combat ceiling' of the Zero, whereas RAAF tests established the Spitfire VC's operational ceiling as 37 000 feet; even weighed down with a full 30 gallon ferry tank, at 35 000 feet the Spitfire was still climbing at 102 knots IAS (173 TAS), going up at 100 feet per minute[3] ('service ceiling' was defined as the altitude at which the rate of climb fell to this value). The superiority of the Spitfire's ceiling is corroborated by its 5000 feet higher rated altitude, by 1 Fighter Wing's demonstrated tactical employment of the Spitfire at heights up to 33 500 feet, and by the Zero pilots' avoidance of the height band above 30 000. The pattern established in these tests confirmed the findings of operational experience over Darwin, where the Spitfires were always able to dominate the upper height band without Japanese challenge.

The Zero developed its maximum speed of 291 knots at its rated altitude of 16 000 feet. The Spitfire produced 290 knots at 15 000 feet, confirming that below 20 000 feet the two types were more evenly matched in speed performance. Given the Zero's much superior acceleration, in practice this meant that the advantage tipped more heavily in favour of the Zero at these lower altitudes. In comparative tests at 17 000 feet, the Spitfire was again unable to safely draw away from the Zero. The unanimous conclusion of Wawn and Jackson was that 'the Spitfire is outclassed by the Hap at all heights up to 20,000 feet'.

As was already well known, the Zero had all the advantages in combat manoeuvrability at slower speeds. This was a product of the Japanese machine's superior power loading and lower wing loading. The Zero stalled at only 55 knots, whereas in clean configuration the Spitfire stalled at 73. Being able to fly more slowly while still under complete control meant the Zero could fly tighter turns without stalling out. The stall speeds cited apply to straight and level flight at 1G – hardly a realistic scenario in combat, where pilots would typica ... reply | | Ron, e-mail, 25.06.2014 00:37 The tropicalized Spit Mk V did battle the A6M3 Zero as well as a few Oscars over Darwin for 5 months with somewhat unsatisfying results for both sides. The Spitfire could beat the Zero up high but that's where the cold sensitive Hispano cannons often failed to perform. Its short range was another very costly limitation. So it wasn't simply a just a matter of Spitfires spinning out of control trying to duel with Zeros. They already learned not to turn with Oscars and Zeros.

The Spitfires at least held their space and the Japanese air raids departed Darwin finally. But Spitfire losses were high. How high were Japanese losses?

The controversy over which side lost what won't be settled here. But the fact is neither side felt very victorious dispite the conflicting claims.

It's amazing that so few people know that the Zero and Spitfire really met in combat.

Over Darwin many aces on both sides were among the pilots so

that was about par. The A6M3 didn't have the reliability problems with their cannons like the Spitfires did. I believe they weren't the low velocity 20mm cannons of the older A6M2 either. It could still turn 180 degrees in 6 seconds flat and out range the Spitfire V by many orders of magnitude surprising the interceptors by their mere presence. If it was the Model 33 Hamp, it had improved roll and speed with clipped wings. This was before the new more powerful Zero engine got weighed down as with following models so its acceleration was still great.

It's no wonder the aging Spit V had its hands full over Darwin. reply | | Neil, e-mail, 08.11.2012 03:44 My Father apprenticed in a machine shop that made the receivers for the machine guns mounted in this aircraft. reply | | Mark, e-mail, 20.09.2012 17:12 Supermarine Spitfire

Το Supermarine Spitfire υπήρξε ένα από τα πιο διάσημα καταδιωκτικά αεροσκάφη όλων των εποχών, σύμβολο της Βρετανικής αεροπορικής ισχύος και χρησιμοποιήθηκε ευρύτατα από τη RAF και τις συμμαχικές αεροπορίες κατά το Β΄ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο και τη δεκαετία του ΄50.

Κατασκευασμένο από τη Βρετανική Supermarine το Spitfire ήταν μια δημιουργία του αρχισχεδιαστή της εταιρείας R. J. Mitchell, που συνέχισε να τελειοποιεί το σχέδιό του μέχρι και το 1937 που πέθανε από καρκίνο. Οι ελλειπτικές του πτέρυγες του επέτρεπαν ανώτερες ταχύτητες από το Hawker Hurricane και άλλους ανταγωνιστές του, του έδιναν δε μία χαρακτηριστική εμφάνιση, ενισχύοντας την όλη του αεροδυναμική εικόνα. Ιδιαίτερα αγαπητό από τους χειριστές του, το Spitfire χρησιμοποιήθηκε καθΆ όλη τη διάρκεια του Β΄ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου και τα αμέσως μετέπειτα χρόνια, σε όλα τα θέατρα του πολέμου και σε πολλές παραλλαγές.

Περισσότερα από 20.300 τεμάχια όλων των τύπων κατασκευάστηκαν, συμπεριλαμβανομένου και ενός διθέσιου εκπαιδευτικού, ενώ κάποια από αυτά συνέχισαν να χρησιμοποιούνται ακόμα και στη δεκαετία του Ά50, όταν τα αεριωθούμενα είχαν πια επικρατήσει. Αν και ο μεγάλος του αντίπαλος, το Messerschmitt Bf 109, το συναγωνίστηκε σε στατιστικά παραγωγής, το Spitfire υπήρξε το μόνο Βρετανικό καταδιωκτικό που παρέμεινε σε συνεχή παραγωγή πριν, κατά τη διάρκεια και μετά το Β΄ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο. reply | | Matt Thrasher, e-mail, 27.03.2012 03:42 "4. The speed of sound does not vary with aircraft attitude."

I think you're almost correct. The speed of sound varies with the density and pressure /temperature of the gas(es) involved. Ask Gen. Yeager why he flew the X-1 in a climb instead of a dive to break 'the sound barrier', if you get a chance.

Regardless, the Spitfire is one beautiful aircraft. reply | | Ron, e-mail, 08.01.2012 07:19 Mk LF IX (3293 kg loaded): (235m radius) 360 degree turn time is put at 17.5 sec.@ 1,000m alt, by some.

Of course that's with clipped wings. reply | |

| | remi riemis, e-mail, 20.12.2011 20:25 this is a great aircraft when i was 15 jears old i saw the first time the spitfire.I live in belgium in the city of antwerp and somethimes at the airport of deurne flys a spitfire and that is great many greetings reply | | Chris, e-mail, 07.06.2011 10:20 A number of points...

1. The speed of sound in air is a function of barometric pressure, temperature and humidity.

2. The figure 761.2 mph is valid only in an ICAO Standard Atmosphere at Sea Level.

3. While the above data would have been available from the recording instruments carried by Flt. Lt. Ted Powles' Spitfire PR-XIX, PS852, the instruments were never designed for recording this data in a very rapidly changing environment such as would have been encountered in a high speed dive. Consequently, the readings are questionable. Without knowing the degree of accuracy available from each instrument, it is impossible to accurately reconstruct the flight's proximity to Mach 1. To be accurately informed as to the accuracy of the instruments, one would need to consult either official documentation or an instrument technician familiar with the types of instruments carried by PS852 on February 5, 1952 out of Kai Tak, Hong Kong.

4. The speed of sound does not vary with aircraft attitude.

5. Different parts of the airframe will have different Mach numbers, owing to local fluctuations in airflow.

6. It was the thin wing cross-section of the Spitfire that gave it a higher critical Mach number than any of its contemporaries, including the early jets. reply | | John V C Fisher, e-mail, 29.05.2011 12:09 I was in the Air Force in 1947 after the war,Group 1 instrument maker, @ No 1 PRFU Finningley.I can remember being upside down in a Spit cockpit working behind the blind flying panel, a tight squeeze. The gun sight filled the front screen space. reply | | Ron, e-mail, 29.05.2011 03:31 Using Mach speed for dives is tricky.

If the Mach 0.891 dive was 606 mph, then that computes to 680 mph for Mach 1. That was in the 1940s

If the Mach 0.94 dive was 680 mph, then it is 715 mph for Mach 1! That was in the 1950s.

Another site online uses 692 mph to convert to Mach dive speed. So forget the post of 761.2 mph I was using before.

It is obviously for level speed.

What does your math say? I could be wrong again.

What should still show is the relative dive performance of the planes, by either measure (mph or Mach). Alas, there are varied results that can be found in contradiction to that line of thinking too.

Then I tend to make excuses like weather, pilot's courage to push the envelope, design stability, and structural strength.

So, if you read some of my posts in the past that seamed off, bear these points in mind. reply | | Mick Skinner, e-mail, 08.03.2011 16:43 I worked on the later versions of this beautiful A /C in 1966 on the Historical Aircraft Flight at RAF Coltishall we had 3 Spitfires and 2 Hurricanes all in great flying condition, they did airshows and practised regularly at Colt doing beat ups down the Lightening pan, I wonder where they are now. I would love to see one at the Reno Air Races to give the P51 Mustangs some competition. The sound of a Merlin on full chat is a sound to behold. reply | | Bill Holmes, e-mail, 03.03.2011 09:59 I am 58 and my father (now deceased) flew spitfires in the 54 squadron. I still have all his flight books and always loved hearing his stories of defending Darwin Australia during later part of the war. He loved Australia so much we moved out here from UK when I was 5 after he returned from the war. reply |

|

Do you have any comments?

|

|

COMPANY

PROFILE

All the World's Rotorcraft

|

Ben De Bie

Ben De Bie

comment1,

reply